Building a simulation-based education session requires several steps to ensure a successful experience for learners, instructors, and technical staff. The Interprofessional Simulation Center follows a stepwise approach based on established learning theory and practice to meet this goal.

This poster outlines the process described below. Also, these development templates will help get you started on your journey to creating your curriculum:

Course Cover Page – This document will provide basic information about the course you are building. Points such as needs analysis, learner analysis, and basic demographic information are recorded here. Each Course Cover Page will have at least one simulation activity associated with it. This can be for a simulation scenario, a simulation skills event, or a Standardized Patient activity, or possibly a combination of the three.

Simulation Scenario Template – The Scenario Template is used for simulation activities that involve a manikin in a dynamic case which typically has a team of care providers.

Skills Station Template – The Skills Template is for setting stations where skills will be practiced. These can be for skills such as IV starts, NG tube placement, or other tasks.

OSCE Template – The OSCE (or Standardized Patient) Template is for use when the simulator is a Standardized Patient.

Center staff are available to help you build your simulation course.

At its most basic, the four questions Ralph Tyler first posed in 1949 still serve as the fundamental building blocks in creating curriculum. Using these as a starting point, the Center’s process builds on with more detail.

The Center’s process melds three frequently used curriculum design models into a single flow that takes strengths from each to create a comprehensive method to build the education experience.

Simulation-based education (just like all education and training) must have a purpose. It should solve a problem or meet a specific need. An educator should ask, “What problem am I trying to solve?”

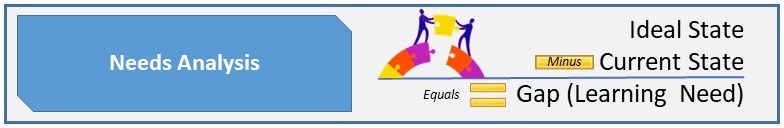

Together with Problem Identification is Needs Analysis. In its simplest form, a needs analysis resembles a mathematical formula – The ideal state minus the current state equals the gap or learning need.

A needs analysis defines the problem at its source. The need may be internal to the learner (just wanting to be their best). It may be data driven (changing an organizational performance metric for the better). It may be operational (introducing new equipment or processes). It may be regulatory (meeting mandated requirements).

Defining the need is an essential step that links to the outcome of the educational intervention in the evaluation step.

Next, Learner Analysis examines the learner group. How do they like to learn? What do they already know? What attitudes do they have about learning? What do they think of the subject?

Understanding the learners’ starting point is critical to building a program that takes them from their current knowledge set to the next level.

Central to this is the concept of the “Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).” Developed by Lev Vygotsky, this concept takes the learner from what they already know to what they can achieve with the right support. An educational intervention, including a simulation, that tries to reach beyond the ZPD may be too big a jump for learners to handle. Built upon the constructivist method of scaffolding, simulation should be a challenge, but one that is achievable.

For more on the Zone of Proximal Development – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_of_proximal_development

Next up is defining the educational goal and learning objectives. The goal is a short overall statement of what the purpose is. This should refer to the original Problem Identification.

Learning Objectives are the steps needed to achieve the goal. There are several models for building objectives. One frequently used model is the SMART objective: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-bound.

For more information on SMART Objectives –

https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/pdf/brief3b.pdf

Another consideration is the type of objective. Benjamin Bloom categorized three Learning Domains: Cognitive, Affective, and Psychomotor. Each examines a type of behavior and is represented in a hierarchy from basic to advanced capabilities. Along with each domain, comes a set of verbs that align with each level to assist in objective development.

For more on Bloom’s Learning Domains – https://educerecentre.com/what-are-the-three-domains-of-blooms-taxonomy/

For a guide on creating objectives developed by Center Director David Rodgers click here

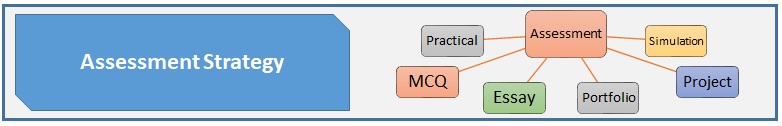

First, some definitions. Assessment looks at what learners’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes are in relation to the learning objectives. Evaluation looks at the program or course and its impact on the initial problem as well as the instructional quality (including teacher effectiveness).

Rather than waiting until the end of the development process, now is the time to build the assessment. Assessments are directly linked to the learning objectives. It is critical to look at the verbs used in the learning objectives. If a verb says “demonstrate,” then a practical assessment may be needed. If the verb says “list,”, then an open-answer written test may be adequate.

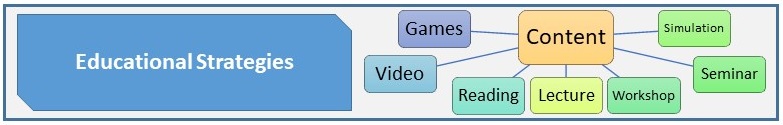

The educational strategy must be matched to the learning objectives and assessment methods. If the objectives are focused on hands-on practical tasks, then the content needs to allow for hands-on demonstration and practice. Filling the content in with lots of lecture and discussion is not going to prepare learners for the assessment to meet the objectives for these practical tasks.

Depending on the learning objectives, more than one strategy may be needed.

Another consideration is looking back at the learner analysis. How do the learners like to learn? The strategy needs to take this into account and may require different strategies to meet different learners’ needs.

For more on learning styles, visit these links –https://www.melioeducation.com/blog/vark-different-learning-styles/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24823519/

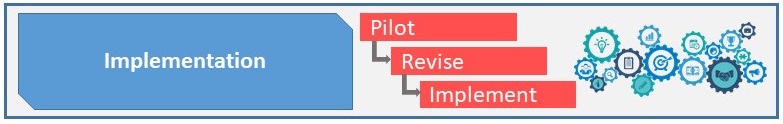

Testing an educational intervention is always well advised, especially if it is a simulation. Even with the most well thought out simulations, there are typically surprises that pop up in the pilot phase that require revisions. Things like a missing medication from the set-up list, a vital sign that did not match the scenario progression, or an unanticipated action by a learner as they experiment in the case. A simulation case is usually in a state of constant revision, particularly looking at the long-term as treatment protocols change or new equipment or supplies become available.

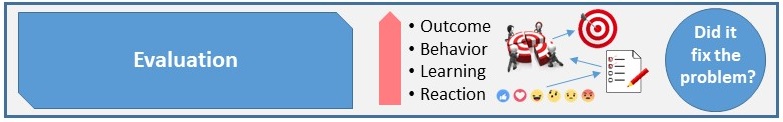

Evaluation, as noted above, is the educational intervention’s impact on the original problem. Fundamentally, did the program make a difference, did it fix the problem? The Center ascribes to the Kirkpatrick evaluation model that examines four levels of evaluation that look at program impact.

Reaction – What did learners think of the program? What was the level of satisfaction with the course or instructors? Was the content worthwhile to them in their professional roles?

Learning – Did the learners learn something new or different? Were the learning objectives achieved?

Behavior – Was the learning demonstrated in the workplace after the course was completed? Did learners use the new knowledge, skills, or attitudes effectively in daily practice?

Outcome – Did the learning intervention have a lasting impact to outcomes critical to the organization?

In the Center, the first step in the evaluation process is for learners to complete the simulation evaluation. There are QR codes posted in each simulation room that take learners to the evaluation survey.

For more on the Kirkpatrick evaluation model – https://icenetblog.royalcollege.ca/2019/05/07/education-theory-made-practical-volume-3-part-4/

What’s Next?

This process is a cycle that continually revisits the original problem identification, revises goals and objectives based on new materials or findings, and takes advantage of new technologies for assessment and content delivery.

To help educators prepare simulations, a course design template is available (Link to Template)

To request a Center assistance in developing a course or simulation, contact the Center at hsbsim@iu.edu.

References:

- Tyler RW. Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1949

- Dick W, Carey L. Carey JO. The Systematic Design of Instruction (8th – Loose Leaf Version). Boston: Pearson; 2015.

- Gagne RM, Wager WW, Golas KC, Keller JM. Principles of Instructional Design. 8th Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson; 2005.

- Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A six-step Approach. 3rd Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

- Bloom B, Englelhart M, Furst E, Hill W, Krathwohl D. Taxonomy of Educationall Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cogntive Domain. New York: David McKay Company; 1956.

- Kirkpatrick, D.L. (1998). Evaluating Training Programs. 2nd San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler; 1998.